Hello friends,

From the advent of cinema to the present day, history has been brought to life on screen in many striking ways that have advanced motion picture technology and forged new relationships between viewers and the historical past. Historical films offer a privileged site for scholars of cinema, media, history, and many other disciplines to interrogate a nation’s relationship with the past. How cinema engages with the past, whether recent or distant, provides interesting case studies for how successive generations renegotiate cultural memory and understandings of how the past shapes the present.

All people are living histories, and if there have been some characters from the past we may not have heard much of, their stories ought to be told. And so, when historians are asked the relevance of studying History, or why on earth does it matter what happened long ago, the inescapable truth about the legacies of past in the present, it helps connect things through time and encourages its students to take a long view of such connections.

Historical films can bring into relief hidden or competing histories that either challenge or compliment prevailing narratives and authoritative accounts of the past, asking the viewer to consider the present as being shaped by multiple histories, rather than by one history.

Thus, history is an immensely important subject to study and understand. It provides the answers to why the world is like it is. An inaccurate understanding of the past, therefore, will present the incorrect answers as to why the world is like it is now.

This blog will study two films The Black Prince and Victoria and Abdul from the Postcolonial theory.

The Black Prince

The Black Prince is a story of Queen Victoria and the Last King of Punjab, Maharaja Duleep Singh, who was torn between two cultures and faced constant dilemmas as a result. Despite his close relationship with Queen Victoria that made him draw into the English culture, Singh or The Black Prince as he was popularly called, began a lifelong struggle to regain his kingdom that took him on an extraordinary journey across the world.

The Black Prince ends up as one big, bland, dull and inert film that kills all its good intentions only because there seems to be no meat, neither in the story nor in its execution, beyond what we already know about the characters.

The youngest son of Maharaja Ranjit Singh, ruler of northwestern India, the “Lion of Punjab” and the only child of Maharani Jindan Kaur, Duleep Singh was crowned at the age of five, but was forcibly exiled to Britain, almost immediately after, where he became a favourite of Queen Victoria. He survived even during the division and bloodshed as four potential successors got killed, and the British watched like “vultures”.

He gets to learn about God, Christianity and other social etiquettes by his guardian, Dr Login, and is told that India benefited by the British rule. He is respectful to all but an uncanny sense of unease begins to discomfort him as he longs to see his real mother, who he is categorically told is “old and too weak to travel”.

Perhaps the latent desire to be with his countrymen also begins to rekindle in him an inexplicable concern for the land of his birth: Punjab. When he gets permission to bring her to England, he gets more and more influenced by her to reclaim his birthright and overturn the escalating oppression of India by British colonialists.

Maharani ends abruptly to make the proceedings even more lifeless.

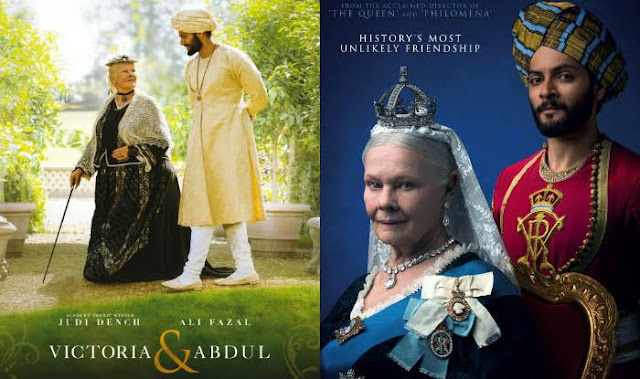

(2)Victoria and Abdul

Despite an uneven narrative and historical inaccuracies, Victoria and Abdul is a delightful film that deserves to be watched.

The movie starts with a note “Based on true events… Mostly” and you wish the makers should’ve excluded the most part of it trying to stick with the true events. The story definitely is earnest but it’s shallow from its heart. Lee Hall’s screenplay gets repetitive after a point where you’ll just wish it to end.

What's wrong with the film is, of converting a fascinating tale into a crawling big yawn.

Many times as Ali Fazal uses the term ‘Her Majesty’

It all starts when a bookkeeper Abdul Karim (Ali Fazal) is sent to England to present a coin (Mohar) to the Empress of India – Queen Victoria (Judi Dench).

“Life is like a carpet, we weave in and out to make a pattern”

– It all starts when Queen bowled over by this tallest man the house presents him to be her personal footman. Queen orders him to teach her Urdu and lessons from the Holy Book of Quran.

Evidently, the entire palace, unhappy with this starts to nitpicking Abdul’s flaws. The members planning on how to get rid of Abdul with some more scenes in which Frears try to build the connection between Queen & Abdul is what rest of the story is all about.

In an initial scene, we see Judi Dench snores while sleeping in the midst of a grand dinner – ironically I found myself in the same position just the dining table was replaced by a movie theatre. The story of the film never settles in one genre, at one point you’ll feel it’s pure drama but immediately a comic scene will follow which will end up being boring. Stephen has made this a mixture of many mundane moments.

Click here to have critical insight for An Era of Darkness. During the previous semester as a part of Sunday Reading Activity I prepared one blog on Shashi Tharoor. It is quite interesting to look upon. I have updated it with few more interesting things.

Ruchi Joshi's blog on Shashi Tharoor 'An Era of Darkness'

Thank You.

References

Schulze, Brigitte. “The Cinematic 'Discovery of India': Mehboob's Re-Invention of the Nation in Mother India.” Social Scientist, vol. 30, no. 9/10, 2002, pp. 72–87. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3517959. Accessed 29 Nov. 2020.

“Studying Film.” Studying Film with André Bazin, by Blandine Joret, Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam, 2019, pp. 17–46. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvrs8xh6.4. Accessed 29 Nov. 2020.

Tharoor, Shashi. An Era of Darkness the British Empire in India. Aleph, 2016.

No comments:

Post a Comment